The Fawn Response: What It Really Is

Most women think they’re “just being polite,” “easygoing,” or “not wanting to rock the boat.” But often, what they call kindness or flexibility is actually the fawn response — a nervous-system survival strategy developed early in life when pleasing others was the safest option. It’s also known as “wearing masks.”

This post explains what the fawn response really is, why so many smart, capable women use it automatically, and how to begin shifting the pattern with awareness rather than shame.

What Is the Fawn Response?

The fawn response is a trauma response in which the nervous system attempts to create safety by appeasing, pleasing, or accommodating others.

It is:

automatic

unconscious

body-driven

learned early through relational dynamics

In fawn, your system believes: “If I keep you happy, I stay safe.” This is not a personality trait. It’s an adaptation — one that develops when someone grows up around volatility, criticism, inconsistency, emotional unpredictability, or caregivers whose moods needed to be closely managed.

Signs You’re in a Fawn Response

You may be in fawn if you often:

say “yes” when you want to say “no”

soften, downplay, or hide your needs

adjust yourself to avoid conflict

take responsibility for others’ emotions

apologize even when you’ve done nothing wrong

become the “easy one” or the caretaker

read the room before you read yourself

feel distressed when someone is unhappy with you

lose your preferences in relationships

defer to others but later feel resentful or depleted

These patterns happen before you can think about them — the nervous system reacts first, the mind explains later.

Why Smart, Capable Women Fawn the Most

The fawn response is not a lack of strength. It often develops in women who are exceptionally perceptive, attuned, and responsible — the ones who learned early how to keep peace, stabilize adults, or avoid conflict.

Women who fawn are usually:

hyper-aware of emotional dynamics

highly empathetic

skilled observers

good at reading needs

conflict-sensitive

socially intelligent

naturally responsible or conscientious

These are strengths — just misapplied in contexts where they become survival behaviors instead of conscious choices. This is why high-performing women can excel everywhere except in relationships, where their survival patterns take over.

The Nervous System Behind Fawn

Fawning is a function of the ventral vagal + fawn overlay, where the body blends social engagement with appeasement to create safety. It’s a cousin to:

freeze (numbing, shutting down)

fight/flight (reactive protection)

Fawn says: “Stay close, stay agreeable, stay small, stay safe.”

Your body is not betraying you. It is trying to protect you based on what it learned long ago.

Where the Fawn Response Comes From

The fawn pattern almost always begins in relationships where a child had to:

manage an adult’s emotions

avoid someone’s anger, criticism, or disappointment

stay attuned to unpredictable moods

become “the good one”

prioritize others’ needs to keep connection

earn safety by being helpful, calm, or pleasing

de-escalate tension or conflict

anticipate problems before they happened

When safety is inconsistent, children learn: “If I’m pleasing, I’m safer.” This pattern continues into adulthood until it’s consciously interrupted.

How Fawning Shows Up in Adult Relationships

In adulthood, fawning often becomes:

difficulty setting boundaries

tolerating discomfort or disrespect

choosing partners you must manage

minimizing your needs to avoid conflict

over-functioning emotionally

attraction to emotionally unpredictable people

feeling responsible for keeping the peace

losing your sense of self in relationships

Fawning is ultimately a self-abandonment pattern — but one that made perfect sense at the time.

How to Begin Interrupting the Fawn Response

You don’t stop fawning by forcing new behavior. You stop fawning by building internal safety so your body no longer believes appeasement is the only option.

Start with:

1. Micro Boundaries

Not huge lines in the sand — tiny shifts:

“No, I can’t this week.”

“I need a moment.”

“I’m not available right now.”

2. Pause Before Responding

If your instinct is immediate “yes,” practice a 10-second pause. It interrupts the autopilot.

3. Feel Your Body’s Signals

Fawn often comes with tension in:

throat

chest

gut

shoulders

Your body knows before your mind does.

4. Name What You Want

Start privately. Then with safe people. Then in neutral conversations.

5. Rebuild Tolerance for Discomfort

Not all disapproval is danger. Your nervous system may need help learning this.

6. Practice Conflict in Small, Safe Ways

Healthy conflict is not dangerous — but your body may not know that yet.

7. Work With Someone Who Understands Fawn

Trauma-informed coaching helps women understand the pattern, slow it down, and build the internal sense of safety needed to choose differently.

Why Coaching Helps With the Fawn Response

Trauma-informed coaching supports women in:

recognizing when fawn is happening

strengthening self-trust

developing boundaries that feel doable

exploring needs and desires without guilt

learning nervous-system regulation

making choices from clarity rather than appeasement

breaking relational patterns that feel automatic

practicing honest communication in a safe space

Coaching works because fawn is about patterns, not pathology — and patterns change through awareness + practice + support.

If You Recognize Yourself Here…

You’re not alone. And nothing about this pattern means you’re weak. It means you adapted. Beautifully. And when you apply the skills you have from these adaptations in healthy ways, they too become superpowers. Now you get to choose something new.

If you’re ready to explore this work, you can learn more about FoxARC Coaching and my 12-week 1:1 program for women rebuilding self-trust.

This content is for educational and informational purposes only. I am not a therapist, counselor, or medical provider. I do not diagnose or treat mental health conditions. For clinical support or diagnosis, please consult a licensed mental health professional.

References

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Conti, P. (2021). Trauma: The invisible epidemic: How trauma works and how we can heal from it. Sounds True.

Fisher, J. (2017). Healing the fragmented selves of trauma survivors. Routledge.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books.

Maté, G., & Maté, D. (2022). The myth of normal: Trauma, illness, and healing in a toxic culture. Avery.

Walker, P. (2013). Complex PTSD: From surviving to thriving. Azure Coyote.

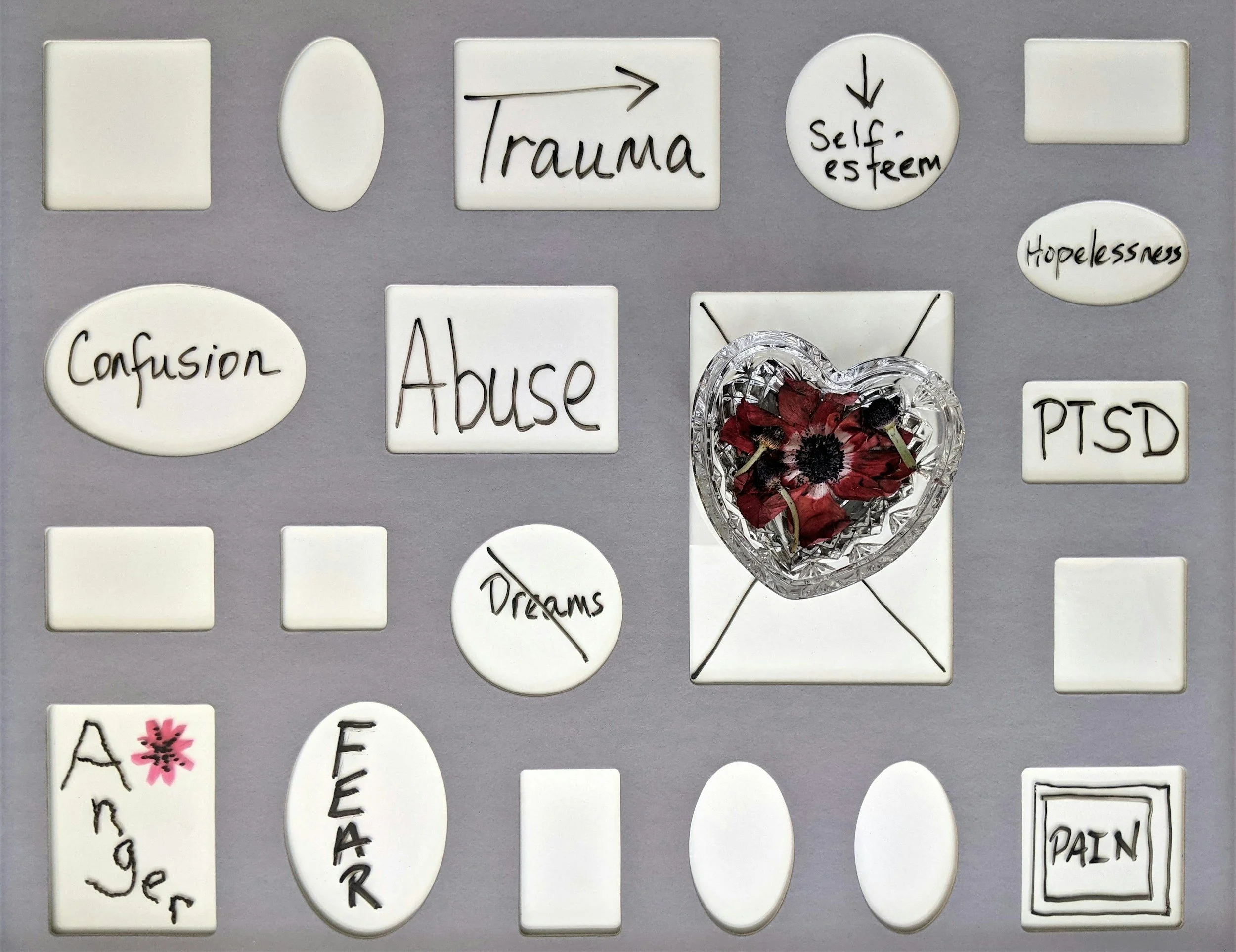

C-PTS: How Complex Trauma Shapes Women’s Lives — And Why Self-Trust Becomes the Way Home

Most women who carry Complex Post-Traumatic Stress (C-PTS) don’t realize that what they’re experiencing is trauma. That’s because C-PTS rarely comes from a single event.

It comes from long-term emotional or relational stress, often in childhood, and often caused by people you trusted — parents, caregivers, family members, teachers, or partners.

When the people who were supposed to provide safety were also unpredictable, volatile, neglectful, or harmful, your nervous system adapted to survive. And those adaptations — not the trauma itself — are what you carry into adulthood.

This blog post explains what C-PTS is, where it comes from, how it shows up in all kinds of women’s lives, and why self-trust is the key to healing.

Most women who carry Complex Post-Traumatic Stress (C-PTS) don’t realize that what they’re experiencing is trauma. That’s because C-PTS rarely comes from a single event. It comes from long-term emotional or relational stress, often in childhood, and often caused by people you trusted — parents, caregivers, family members, teachers, or partners. When the people who were supposed to provide safety were also unpredictable, volatile, neglectful, or harmful, your nervous system adapted to survive. And those adaptations — not the trauma itself — are what you carry into adulthood.

This blog post explains what C-PTS is, where it comes from, how it shows up in women’s lives, how coaching supports healing, and why self-trust is the path forward.

What Is C-PTS?

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress (C-PTS) develops from chronic, repeated, or inescapable relational stress, not from one crisis moment.

Examples include:

emotional abuse

neglect

gaslighting

unpredictable parenting

criticism or coercion

betrayal by trusted caregivers

ongoing conflict or instability

unsafe or inconsistent homes

Most C-PTS is formed in childhood, when the brain and nervous system are still wiring for attachment, identity, safety, and belonging.

When the source of harm is also the source of care, the nervous system learns contradictory rules:

Love is unpredictable.

Safety depends on someone else’s mood.

My needs are secondary.

I must perform, please, or adapt to stay connected.

These rules don’t disappear when you grow up — they just take new shapes.

C-PTS Isn’t a Disorder — It’s an Adaptation

C-PTS is often mislabeled as:

anxiety

depression

“being dramatic”

codependence

conflict avoidance

perfectionism

overthinking

emotional sensitivity

But these aren’t flaws. They are intelligent coping strategies that once helped you survive. Your body learned how to stay safe long before you had conscious choice.

Core Nervous System Adaptations in C-PTS

Shutdown – Numb, blank, or disconnected.

Overwhelm – Emotional flooding; too much too fast.

Fawn – Pleasing or smoothing conflict to stay safe.

Freeze – Stuck, silent, unable to act.

Fight or Flight – Pushing back or escaping to protect yourself.

These are survival responses — not personality traits.

How C-PTS Shows Up in Everyday Life

C-PTS doesn’t affect one “type” of woman.

It affects women across all backgrounds, temperaments, identities, and strengths.

The patterns vary, but the roots are the same.

1. Relational Patterns

Women with C-PTS often:

choose partners who replicate early emotional patterns

confuse unpredictability with passion

mistrust steady, consistent people

feel responsible for others’ emotions

struggle to name needs or set boundaries

lose clarity in conflict

feel guilty for wanting more

stay too long in relationships that hurt

None of this is weakness — it’s pattern memory.

2. High-Functioning Adaptations (Common but Not Required)

Some women respond by becoming:

over-achievers

perfectionists

caretakers

fixers

performers

hyper-independent “strong ones”

the emotional manager in every room

Achievement becomes protection: “If I excel, I won’t be abandoned.”

3. Under-Functioning Adaptations (Equally Valid)

Other women respond by:

collapsing under pressure

struggling to finish tasks

feeling overwhelmed by daily demands

losing momentum easily

battling fatigue, shutdown, or freeze

feeling foggy, scattered, or disorganized

This isn’t laziness — it’s nervous system depletion. Both patterns — over-functioning and under-functioning — come from the same root:

your body did what it had to do to survive.

4. Emotional Patterns

Common emotional signatures include:

chronic shame

confusion that masks fear

difficulty trusting perceptions

fear of conflict

fear of abandonment

trouble relaxing

fear of being “too much”

This is the internal world shaped by early inconsistency.

5. Trauma Bonding

A simple definition: Feeling attached to someone who also hurts you, because the highs and lows get wired into your sense of love and safety.

6. Body-Based Patterns

C-PTS lives in the body. Women often describe:

tight chest or throat

digestive issues

chronic tension

anxiety in intimacy

freeze during conflict

exhaustion that feels emotional

numbing out

difficulty feeling desire or joy

The body remembers what the mind learned to minimize.

Why Self-Trust Is the Key to Healing

C-PTS disrupts your internal compass. It makes you doubt your perceptions, your intuition, your boundaries, and your truth.

Healing C-PTS isn’t about “getting over it.” It’s about restoring the connection to yourself that trauma fractured.

This means learning to:

trust your body again

recognize survival patterns

listen to intuition

honor your needs

build internal safety

cultivate steadiness

choose relationships that support regulation

reclaim agency and desire

replace survival with sovereignty

This is the heart of the Heroine’s Path.

And it is why my coaching centers around one truth: Self-Trust Is Your Superpower.

How Coaching Helps With C-PTS (Without Being Therapy)

Coaching is uniquely effective for C-PTS because most of the pain shows up in the present — in relationships, communication, boundaries, self-trust, identity, and the nervous system.

Here’s how trauma-informed coaching supports this work:

1. Coaching restores self-trust

You learn to hear your intuition again, trust your perceptions, and rebuild your inner compass.

2. Coaching identifies survival patterns

Over-achieving, shutting down, fawning, fixing — coaching makes the invisible visible.

3. Coaching provides a corrective relational experience

It’s not therapy — and it’s not meant to replace therapy — but relational safety, consistency, curiosity, and non-judgment.

4. Coaching builds nervous system awareness

You learn what’s happening in your body in real time — and what choices are available.

5. Coaching focuses on the present and future

Boundaries, identity, communication, values, agency — these are coaching domains.

6. Coaching transforms your narrative

Through the Heroine’s Path, coaching helps you rewrite your story from survival to sovereignty.

Coaching doesn’t diagnose C-PTSD.

What it does do is help with the patterns trauma leaves behind — patterns that shape your daily life, relationships, and sense of self, so you can heal forward into the life that has been calling to you.

If you see yourself in this…

You are not broken.

You adapted brilliantly.

Now you get to evolve.

If you want to explore this work inside an embodied, narrative-driven coaching process, you can learn more at FoxARC Coaching.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Fisher, J. (2017). Healing the fragmented selves of trauma survivors: Overcoming internal self-alienation. Routledge.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books.

Perry, B. D., & Szalavitz, M. (2006). The boy who was raised as a dog: And other stories from a child psychiatrist’s notebook. Basic Books.

Perry, B. D., & Winfrey, O. (2021). What happened to you? Conversations on trauma, resilience, and healing. Flatiron Books.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton.

Walker, P. (2013). Complex PTSD: From surviving to thriving. Azure Coyote.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

World Health Organization. (2019). International classification of diseases 11th revision (ICD-11). World Health Organization.

Disclaimer: This content is for educational and informational purposes only. I am not a therapist, counselor, or medical provider. I do not diagnose or treat mental health conditions. For clinical support or diagnosis, please consult a licensed mental health professional.